Lost Angeles: Understanding LA's out-of-control homeless issue

Lost Angeles: City of Homeless

FOX 11's documentary, Lost Angeles: City of Homeless, takes a close look at the out-of-control homeless issue in Southern California.

LOS ANGELES - Homelessness in Los Angeles is a complex issue that's been around for decades. Many have tried to fix the problem, but the numbers increase year after year.

FOX 11's new documentary Lost Angeles: City of Homelessness takes a look at the roots and causes of homelessness, arguably the largest issue currently facing Angelenos.

FOX 11 spoke with experts on homelessness and those experiencing homelessness themselves on how we got here and how we can make progress toward solving the issue.

Los Angeles, California. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

The history of homelessness in LA

The history of homelessness in Los Angeles goes back nearly 150 years, to the late 19th Century.

The introduction of rail lines to the now infamous Skid Row neighborhood brought with it seasonal workers looking to capitalize on the industrialization of the area, many of whom were poor. While many cheap hotels and other housing options sprouted up in the neighborhood, many more lived in "house courts" — groups of makeshift wooden structures clustered together in the same lot. Some were living in chicken houses, or cramped on the floors of structures. According to a 2021 report from UCLA, by 1910 approximately 9,800 people lived in these "house courts."

Such living conditions were predictably poor, leading the Housing Commission of the City of Los Angeles to label "house courts" threats to public health. The Commission "abolished, demolished or vacated nearly 200 courts between 1910 and 1913," according to the UCLA report, effectively removing residents from their homes.

Decades later, The Great Depression of the 1930s forced thousands of Americans out of their jobs and into homelessness. The effects were particularly felt in LA. Nearly 25% of white Angelenos lost their jobs during the Depression. For Black Angelenos, that number doubled. But the burden of the rest of the nation was being brought to LA as well. According to the LA Chamber of Commerce, many displaced farmers and workers from the American Midwest and South came to LA. Skid Row’s proximity to the rail station meant the area was many transplants’ first point of contact with the city, and therefore where they settled.

Many of the area’s homeless services have historically centered around the Skid Row area, and much of the services were segregated along sexual and racial lines. Combined with decades of housing discrimination and other racist policies, Black Angelenos were disproportionately represented in the area’s homeless population. According to data from the Los Angeles County Department of Charities from the 1950s, Black men made up more than 5% of the county’s population, but more than 17% of sampled relief applicants. Nearly 60% of those surveyed didn’t have a place to live.

Because of a combination of factors — primarily abundance of and access to cheap hotels, short-term labor and social services — Skid Row became a center for the low-income population. But in the ‘60s, the city discovered many of the hotels in the neighborhood weren’t up to code, and many were demolished. According to the Chamber of Commerce, more than 15,000 units were torn down between the 1960s and 1970s, roughly half of the housing in the area, further exacerbating housing access.

Similar themes emerged throughout the subsequent decades — economic downturns, mass migrations, and a lack of affordable housing led to more and more homelessness. But, while Skid Row may have been the face of the issue, these experiences pushed people out of their homes all over. In 1990 the U.S. government attempted to count the number of people experiencing homelessness across the country. Many criticized the attempt, the Los Angeles Times calling it, "at best… a hit-and-miss operation." The survey claimed just 11,790 homeless people lived in Los Angeles. For comparison, a count conducted by a private group a year later estimated the total to be near 60,000 (though that figure has also faced its share or criticism). One report from the Times attributes the discrepancy to the government’s counting method - looking for the homeless only in shelters and skid rows.

Where are we now?

Now, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development requires cities across the country to conduct an annual homeless count. In LA, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority is in charge of the count. According to the authority's latest numbers, which were gathered in 2020 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the county's homeless population increased by 12.7% over the previous year, while the city of Los Angeles' homeless population jumped by 14.2%.

In January 2019, LAHSA counted 58,936 people experiencing homelessness in LA County. By January 2020 the number rose to 66,433 (an increase of nearly 13%). The city of LA's homeless count jumped by more than 16% over that same time period.

HUD waived the count requirement in 2021 due to a spike in COVID-19 cases. The agency's latest count began in February 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic's effects on homelessness, both in the city of Los Angeles and throughout the county have yet to be fully realized, but LA County Sheriff Alex Villanueva says LA can expect that number to be much higher.

"That 67(,000) number is low," he said. "It’s closer to probably 83,000 because… it was rising by 14% per year like clockwork. They stopped counting in 2020. So today, presume it’s way north of 80,000."

Who is unhoused?

Angelenos are surrounded by homelessness. Los Angeles is a highly desired city that is simply not affordable as rent continues to climb, along with a skyrocketing real estate market. From tents on the freeway and in neighborhoods, to witnessing people on the street while out running errands or leaving dinner at a popular restaurant, it’s part of the culture.

Homelessness can strike at any time, and it does not discriminate.

Homelessness can affect anyone

Many vulnerable populations, such as women who've experienced domestic violence and former foster children, make up a large chunk of LA's homeless population.

"No story is the same. It could be anywhere from my dad, a nine-year-old boy praying beside the only bed that he had at the time for his mom to return home, hanging on to the neck of his dad as his dad made the choice to jump on a freight car and move to California," Rev. Andy Bales, President & CEO of Union Rescue Mission said. "It could be a woman who calls a cab and comes through our front door with all of her belongings and five kids escaping domestic abuse. It could be a little old lady who's been abandoned by her family."

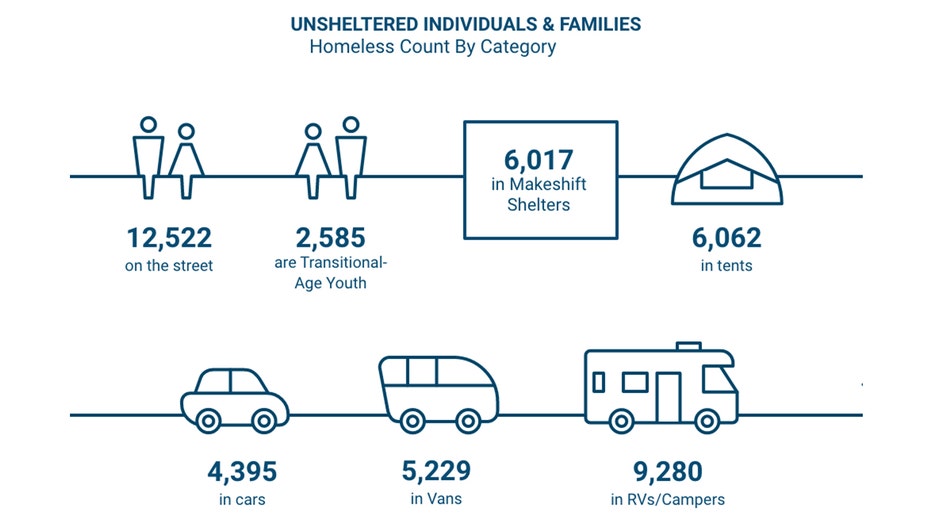

The majority of those experiencing homelessness call the street home. However, there are multiple ways of living that fall under the homeless umbrella. Below is a breakdown of how those fighting for survival sleep at night, according to the 2020 homeless count:

- 12,522 are on the streets

- 2,585 are transitional-age youth

- 6,017 are in makeshift shelters

- 6,062 are living in tents

- 4,395 are living in their cars

- 5,229 are living in vans

- 9,280 are living in RVs

Credit: LAHSA

The year-over-year numbers from 2019 to 2020 are shocking. In the city of Los Angeles, there was a 16% increase from 35,550 to 41,290 residents experiencing homelessness and, in LA County, there was a 13% increase from 58,936 residents to 66,426.

In the Southern California region, Kern and San Bernardino counties saw the biggest spike in their homeless populations in 2020.

Below is a breakdown of the homeless population by race:

- Hispanic/Latino: 36.1%

- Black/African-American: 33.7%

- White: 25.5%

- American-Indian/Alaskan Native: 1.1%

- Asian: 1.2%

- Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 0.3%

- Multiracial: 2.1%

While the homeless crisis impacts people of various backgrounds, the numbers indicate African Americans are affected by a disproportionate rate, which the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority attributes to systemic racism. Black Americans make up for nearly 34% of those experiencing homelessness in LA County, despite being 8% of the population.

"When Los Angeles was developed and at this first half of the last century, there were laws passed that were in the books that decided who lived where. And so if you were a person of color, you were prohibited from buying homes, in particular neighborhoods," Miguel Santana, president and CEO of the Weingart Foundation, explained.

"The 10 Freeway was built on top of a thriving African-American and Latino community in Los Angeles. So over time, the compounding effect of that has been that the wealth that the African-American community could experience was limited and wasn't permitted, and the laws actually allowed it. It’s not surprising that today that a disproportionate number of people experiencing homelessness are African-American," he said.

RELATED: Sugar Hill: The dark history the 10 Freeway has to a historic Black community

Seniors over the age of 62 who became homeless increased by 20% during the pandemic.

"When you turn a certain age in life, they start putting you in a box and those jobs for older people that you could count on, they don't, they don't deal with that anymore. It was left for the young people. My husband is a veteran and he worked hard for what he does and how he does it, but things didn't work out that way," said Geraldine Simpkins.

Officials say while more people are becoming homeless, more is being done to get people off the streets. LAHSA said its focus is to move the 15,000 most vulnerable, including Project Roomkey residents, into permanent housing.

Where is the money?

That’s the billion-dollar question. Literally.

Los Angeles has dedicated a bunch of money to try and combat the homeless crisis. For example Measure H, the 1/4-cent sales tax approved by LA County voters, is expected to raise about $355 million every year for the next decade according to the County. The county then uses that money on things like interim and permanent housing, as well as homeless prevention.

Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority works with about $600 million every year. That money comes from federal, state, county and city funds. According to the administration, 27.2% of that money ($163.2 million) goes to rapid rehousing; 25.6% of it ($153.6 million) goes to housing placements; 30.8% of it ($184.8 million) goes toward shelters; 9.4% ($56.4 million) to homeless outreach services and 7% ($42 million) toward administrative costs.

In May 2022, the LA City Council approved a budget proposal for the 2022-2023 fiscal year that included $1 billion dedicated to homelessness initiatives, which includes:

- $377 million for permanent supportive housing

- $208 million for the Project Homekey program

- $50 million for supportive services

- $17 million for interim housing

Another $5 million will go toward expanding The CIRCLE initiative, a program in Hollywood and Venice that sends homeless service advocates to nonviolent 911 calls involving those experiencing homelessness. The proposed budget would also expand a city program dedicated to cleaning encampments. Once the Council approves budget revisions it will be sent to Mayor Eric Garcetti’s desk for approval.

What is Prop HHH?

In 2016, Los Angeles voters overwhelmingly approved Proposition HHH. The bond measure enabled City officials to issue $1.2 billion in order to create 10,000 permanent supportive housing units for people experiencing homelessness.

Permanent supportive housing combines affordable rent with other resources such as access to job training, mental health services, and drug treatment, giving formerly homeless individuals a better chance at staying housed.

Additionally, the bonds can be used to help build temporary shelters.

Prop HHH received the support of a variety of organizations in addition to public and private stakeholders, including labor unions and private and nonprofit housing developers.

But, six years later, a little more than 1,000 of the 10,000 permanent housing units have been built, according to an audit from LA City Controller Ron Galperin.

"Can you imagine being an outreach worker and going to an encampment and saying, listen, I've got great news for you. We've just passed a bond measure. We're going to create affordable and permanent supportive housing to help you just hang in there for the next four years," said Ken Craft, Founder and CEO of Hope of the Valley Rescue Mission.

Building prices have also increased per unit, Galperin said. What used to cost $375,000 is now averaging $600,000 to $700,000.

"I think if the voters were told that there is no limitation on how much a unit could cost and most of them would be built in the second half of the ten years, not the first half. I think most voters would have thought twice before supporting it," said Miguel Santana, a critic of Prop HHH and a member of the Civilian Oversight Committee.

"We’re projecting one of those projects is actually going to be almost $840,000 if it’s taking three to six years to build and taking that long. Then how are ever going to make a big enough dent in this terrible crisis that we have of homelessness on our streets?" Galperin said.

RELATED: LA spending up to $837,000 to house a single homeless person

Why is it taking so long for these projects to be completed? A few factors, according to Galperin.

First, there are several sources of funding, each with their own requirements and its own lawyers and consultants, Galperin said.

"It takes years until a project can actually break ground. That adds a lot to the cost. We’ve also seen, of course, the cost of everything has gone up, particularly in this last year-and-supply chain problems," he said. "But we knew these problems existed even before COVID happened, and we need to find a way to create a lot more units a lot more cost-effectively."

Miguel Santana, president and CEO of the Weingart Foundation, explained, "So each unit has a layered cake of different funding streams from the state, federal government, through tax credits, some of them from philanthropy. Each one of those funding streams have different priorities, have different expectations, different timelines."

"When you have a lot of regulation on top of regulation and rules on top of rules, it takes more time and costs more money. Look, I'm all for reasonable regulation. That's a good thing. But this is way too much of a good thing," Galperin said.

Santana called Prop HHH a "very clean and straightforward way of supporting the development of permanent, supportive housing."

"What complicated it and what has driven up the costs is how it was implemented and that it required the complicated revenue streams which HHH didn’t require when the voters passed it," he said.

Santana described it as a learning opportunity to "establish clear boundaries around cost [and] clear boundaries around time."

"If there’s a housing development that is funded by HHH with the sole purpose of getting people off the street, then it has to be approved through the bureaucratic process within a certain timeframe," he said.

While only 1,040+ units have actually been completed, Galperin said the impact it is making on the individuals living there is profound.

"Each life we’re able to save, each life that we can improve, each person in each family, that we’re able to get into better shape the better," Galperin said. "If you look at it on the micro-level, it’s very powerful."

Measure H

Measure H was approved by almost 70% of Los Angeles County voters on March 7, 2017. It is a 1/4-cent sales tax to raise a projected $3.5 billion over 10 years for preventing and combating homelessness.

Proceeds from the tax are used to generate ongoing funding to prevent and combat homelessness within Los Angeles County, including homeless prevention, street outreach, supportive services and employment, shelter, and housing.

Measure H’s early prevention to prevent chronic homelessness features two approaches: providing rapid re-housing and addressing transitions out of institutions.

According to the Health Impact Assessment report, participants may have trouble remaining stably housed in the long term. There is evidence showing the benefits of greater collaboration between the criminal justice system and mental health/substance use disorder professionals.

It is designed to fund a comprehensive regional approach encompassing 21 interconnected strategies in six areas to combat homelessness:

- Prevent homelessness

- Subsidize housing

- Increase income

- Provide case management and services

- Create a coordinated system

- Increase affordable/homeless housing

The key strategy is permanent supportive housing, using it as a foundation for aiding recovery.

To ensure accountability, an independent auditor conducts annual audits, and a Citizen’s Oversight Advisory Board reviews all expenditures and submits periodic evaluations.

According to the LA County Homeless initiative, just over 78,000 formerly homeless people have been placed in permanent housing between July 2017 and December 2021, with roughly 40% of those being housed because of funds from Measure H.

"In order for someone to be the most successful in permanent, supportive housing, you need not only a roof over their heads, but you also need the services that help those individuals start dealing with the issues that contributed to their homeless situation in the first place," said Miguel Santana, president and CEO of the Weingart Foundation, which supports nonprofits throughout Southern California.

Santana described Measure H as "part of the answer for everyone experiencing homelessness, but to make a significant investment for everyone experiencing homelessness."

"It was intended to be a response to the crisis that Angelenos were seeing every day," he said.

Project Roomkey and Project Homekey

Project Roomkey is a state program that uses hotels and motels as temporary shelters for people experiencing homelessness.

The program started in April 2020 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus of the program was to help shelter the most vulnerable and at-risk people.

According to California Gov. Gavin Newsom, by June the state was able to house 14,200 individuals.

Before the pandemic, the governor's State of the State Address focused on homelessness and despite a $52 billion deficit following the coronavirus outbreak, the governor has said he managed to find the funding for this plan. That includes $550 million to buy properties and $350 million for services to effectively transition people off the streets and into homes.

Project Roomkey units are intended to be temporary, emergency shelter options, while also serving as a pathway to permanent housing.

Project Homekey builds upon Project Roomkey, which was an urgent, but temporary, initiative to bring seniors and other medically vulnerable people experiencing homelessness indoors to prevent the spread of COVID-19 through leasing hotel rooms.

According to the county, Los Angeles is receiving $108 million in funding. The County is contributing funds from local, state, and federal sources "to complete each acquisition and operate the facilities as interim housing." Some housing units will be renovated into permanent supportive housing.

The address of each Project Roomkey site is confidential. Only people who meet the requirements and are referred through appropriate channels can participate. Project Roomkey sites are not walk-up facilities.

Different approaches to addressing homelessness

Homelessness Prevention

Services that target Homeless Prevention aim to help rent-burdened, low-income families and individuals resolve crises that would otherwise cause them to lose their homes. Among these services include short-term rental subsidies, housing conflict resolution and mediation with landlords and/or property managers, and legal defense against eviction. Similar services are offered to help individuals avoid becoming homeless after exiting institutions like jails, hospitals, and foster care.

Outreach

Outreach teams in the county hit the streets in order to build relationships with those experiencing homelessness with the goal of hoping to connect them to housing, healthcare, mental health treatment, and other services.

Housing

"There's multiple factors that causes a person to be homeless. And until we actually address those factors, homelessness will remain. But the one thing that we can fix in the short term is the permanent housing situation. And that's one thing that we do need to focus on," said Skid Row historian, Dr. Doug Mungin.

- Interim Housing

Interim Housing provides safe temporary accommodations for people who otherwise have nowhere to spend the night. LAHSA’s 2021 Housing Inventory Count found the LA region’s homeless shelter capacity on any given night is 24,616 beds.

- Permanent Housing

Permanent Housing strategies provide either short or long-term rental subsidies to people experiencing homelessness along with Intensive Case Management Services (ICMS) to individuals who have experienced chronic homelessness and have disabilities, chronic medical conditions, and/or behavioral health conditions.

According to LAHSA’s 2021 Housing Inventory Count and Shelter Count, permanent housing slots throughout the LA region increased 16% to 33,592 slots over the last three years. Meanwhile, placement of clients into permanent housing increased 74% on an annual basis between 2015 and 2020.

- Affordable Housing

Lack of affordable housing is one of the primary drivers of homelessness in Los Angeles County. The county’s approach to addressing affordable housing is by pursuing three P’s:

- Production of new affordable housing;

- Preservation of existing affordable housing; and

- Protection of tenants and related supportive programs, including pathways to homeownership.

Empty city-owned land

In May, Los Angeles Controller Ron Galperin urged officials to take advantage of empty, city-owned land to house people experiencing homelessness, adding that he's identified 26 city properties that could be used to house thousands of people. The 26 properties he identified would provide an additional 1.7 million square feet of space for interim housing. The locations could support tiny home villages, safe parking and safe camping areas as well as support facilities such as restrooms, showers and laundry centers, Galperin said.

People can look at a map of the properties at lacontroller.org/audits-and-reports/city-owned-properties.

RELATED: LA controller calls for city to use empty city-owned land to house homeless

Supportive Services and Employment

Some leaders think that simply providing housing for the homeless isn’t enough – that housing needs to be supplemented with services that help alleviate some of the causes of homelessness.

Brittany Walker, CEO of Butterfly’s Haven, was once homeless herself after fleeing a domestic violence situation. She feels that the focus shouldn’t just be on housing, but on "supplying [the homeless] with whatever supportive service that they may need" because every situation is different. Her organization provides shared housing, supportive services and 24-hour childcare for single mothers and former foster children who are experiencing housing instability.

Los Angeles County also offers several social services for people who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless, many of which are funded in part by Measure H.

The Countywide Benefit Entitlement Services Teams pair advocates with disabled people to help them apply for benefits programs or even get health and mental health care. Other programs pair people with criminal records with public defenders to help them navigate legal issues that can be a major barrier to securing housing. For those who need work to help earn enough money for a place to live, there are programs that place people in transitional jobs with robust training programs, that help participants get placed in higher-paying jobs down the road.

Walker says she wants all the women she helps at Butterfly’s Haven to, "leave with a credit score of 700 or better. Go purchase your home from here."

"If you need mental health services, if you do need other supportive services with regards employment or whatever it is that you need, let's address that so that you can logistically soar throughout life," she said.

How you can help

There are several ways to help those experiencing homelessness.

If you know someone who needs services, you can visit the Los Angeles Homeless Outreach Portal (LA-HOP) to submit an outreach request.

According to LAHSA, you can help by advocating for state legislation to establish permanent funding, remove land use and zoning barriers to create affordable units, and remove barriers for people exiting the criminal justice system.

You can also help by doing hands-on work such as volunteering at a homeless shelter or helping to build affordable housing.

The Los Angeles County Development Authority launched a loan pilot program that provides homeowners in unincorporated LA County with a forgivable loan of $75,000 to construct new ADUs (accessory dwelling unit), and $50,000 for rehabbing existing unpermitted ADUs that will house people transitioning out of homelessness for a minimum of ten years.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the YMCA offered access to free hygiene products, showers, bathrooms and locker rooms to unhoused Angelenos. The services were offered at seven various locations throughout the city.

Interactive digital visualizations by FOX 11's Joe Calabrese. FOX 11's Alexa Mae Asperin, Alexandra Chidbachian, Kelli Johnson, KJ Hiramoto and Mary Stringini contributed to this report.