Sex offender in Marin County will be turned out on streets; unlikely allies say that’s not safe

Sex offender in Marin County will be turned out on streets; unlikely allies say that’s not safe

A 68-year-old registered sex offender has no time left on his stay at a Marin County hotel and his case manager is making an unusual plea for someone to house his client so that he doesn’t have to sleep in a tent under a freeway.

SAN RAFAEL, Calif. - A 68-year-old registered sex offender has no time left on his stay at a Marin County hotel and his case manager is making an unusual plea for someone to house his client so that he doesn’t have to sleep in a tent under a freeway.

"The day I get released, I’m supposed to be on the street with diabetes," said Socorro de Jesus Mayen Alvarado, whose first language is Spanish. He is a registered sex offender who served three years in prison after being convicted for molesting his girlfriend’s nieces more than a decade ago. He is on parole for another year and a half.

Then, pointing to his ankle monitor, he said: "And I have no place to charge the device."

While there are some unusual aspects of Alvarado’s story, it's exposed a pretty common debate over the release of sex offenders: There are those who don’t want sex offenders living near their homes and children and feel they shouldn't receive any help or compassion for what they did in the past. And there are those on the other side, who believe that society should do everything they can to help and rehabilitate all those with criminal pasts, even those who committed sexual offenses.

However, despite these stark philosophical differences, there are at least two things these unlikely allies do agree on: Giving sex offenders stable housing cuts down on recidivism rates and knowing where they are living is better for public safety.

"If we're going to let them out, we should let them out somewhere where we can keep track of them," said Michael Rushford, president of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, a conservative group that supports policies that improve law enforcement and the rights of crime victims. "And that's not happening. So from just a pure public safety standpoint, we should be keeping an eye on this person."

Rushford said he believes the best answer is to provide housing for sex offenders so that they can all live together in one place, like a specially designated apartment building or halfway house.

It is soon going to be much harder to keep an eye on Alvarado.

That’s because his month-long stay at the Extended Stay in America in San Rafael runs out on Thursday, and Alvarado will likely be turned out to the streets.

Alvarado is a diabetic, takes a slew of medications from cholesterol to depression, holds down a part-time job at a Chevron station and for the last month, has lived at the hotel, paid for with grant money from the Bay Area Community Resources.

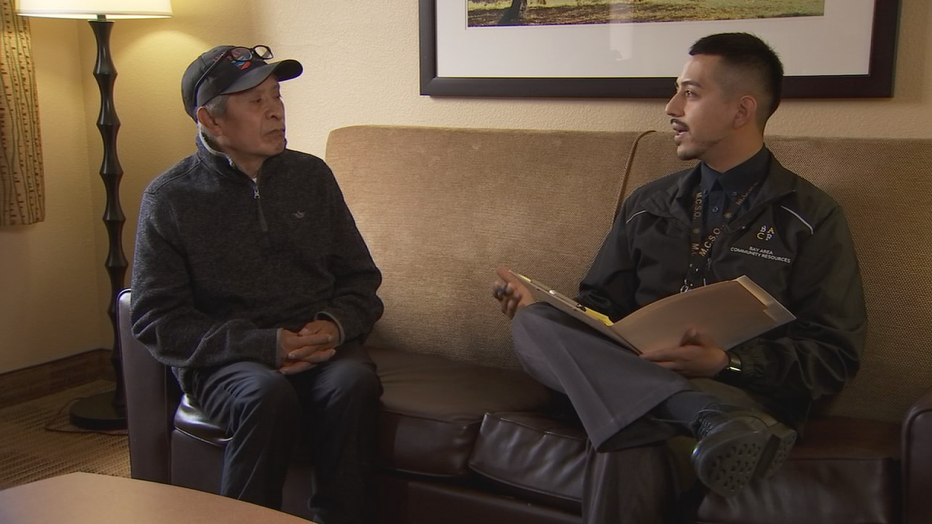

Socorro Mayen Alvarado, 68, talks with his case manager, Dennis Villalobos Sabino, at the Extended Stay Hotel in San Rafael. Aug. 24, 20121

Shelters won't take in sex offender; insurance won't pay

Over the last two weeks, BACR re-entry case manager Dennis Villalobos Sabino has called dozens of homeless shelters and churches to put up Alvarado.

While some didn’t have room or never called back, other shelters directly told Sabino that they wouldn’t house a registered sex offender.

"Because of this status, they rejected us," Sabino said. "I keep getting the same story. The 290, the 290, the 290, the 290, the 290," in reference to California’s penal code that requires sex offenders to register with the state. "They’re rejecting him and closing doors on him. I’m all out of options at this point."

Mary Kay Sweeney, executive director for Homeward Bound, one of the shelters, said that she doesn't take in sex offenders because "we can't get insurance for it. And that's true for a lot of shelters."

She added that her "heart goes out to people" who can't find homes and "obviously, we feel badly." But ultimately, she said, shelters are congregate settings with multiple people and she has to look out for the safety of the entire group. Without mentioning his name specifically, Sweeney said she hoped that Alvarado could find private housing.

Sex offenders can sometimes find rooms to rent in private homes, experts say, but often resort to living in their cars if no one will take them in.

Sabino took the unusual step of reaching out publicly to cry out for help on his client’s behalf, hoping someone would step up and provide housing for him.

On the Megan’s Law database, Alvarado’s risk assessment to re-offend is extremely low: He's ranked a -1, out of 12.

The mission of a re-entry program is to find jobs, housing

Sabino believes it’s a moral obligation for society to help rehabilitate everyone no matter what they did in the past, guilty or not.

And as a re-entry case manager for the Marin County Jail, he said his job is to get people back on their feet and be productive members of their communities, which means finding them jobs and housing.

"Our mission is not complete as a reentry department if we can’t provide housing," he said. "He’s going to be out of hotel on 26th of August and the re-entry department just says to put him out in the tent on the freeway."

He pointed out that it’s more likely that Alvarado will return to jail as he can’t charge his GPS ankle monitor if he’s living on the street and will get dinged by his parole officer for not complying with a myriad of requirements. During the pandemic this is harder for many people on parole, as libraries and other public centers have been closed.

Alvarado also needs to register with the city every 30 days, which will be more difficult, Sabino said, if he doesn’t have a fixed address.

"Because you’re not complying it will put you back in jail and I feel like it reverses all the progress," Sabino said.

Parts of Jessica's Law overturned

In 2017, California’s Supreme Court overturned restrictions on where sex offenders could live as a way to increase housing options and allow law enforcement to better track them. The justices specifically overturned a component of Jessica’s Law, which had once banned sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of schools and parks - a ruling that effectively blocked them from living in most cities.

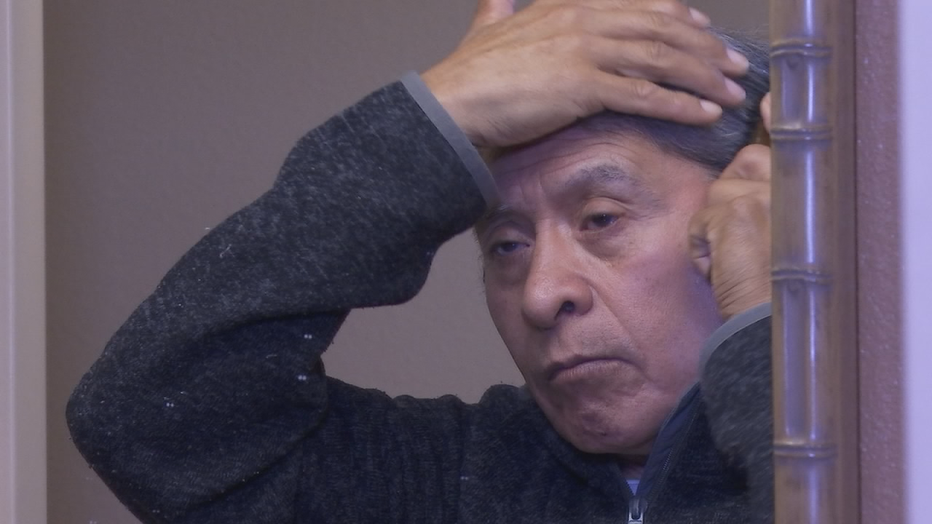

Socorro Mayen Alvarado, 68, brushes his hair at the Extended Stay Hotel in San Rafael. Aug. 24, 20121

The justices agreed with experts who said stable homes, jobs and family ties are important to deter new crimes. Moreover, the court found that when offenders lack permanent homes, it's tougher for law enforcement officers to track their locations and activities.

A 2016 study by U.S. and Canadian researchers and California's Justice Department found offenders who are transient were several times more likely to commit new sex crimes. Only about 6 percent of registered California sex offenders have no permanent address, but that group accounts for 19 percent of new sex crime arrests among those on probation and one-third among those on parole.

Lawyer sues cities over tough living restrictions

Still, cities in California had -- and still have -- laws that prevented sex offenders from living in their communities, and California Reform Sex Offender Laws President Janice Bellucci, an attorney, sued 45 of them. She has won 44 of those cases.

"It is not legal to ban a person on the registry from living in a shelter or an apartment complex or any other place," she said. "In California, a person on the sex offender registry who was not on parole, probation or supervised release can live anywhere in the state they wish to."

She agrees with Rushford, from the crime victims' group, that it’s better to house sex offenders than to shun them.

"Society benefits greatly from housing people who are on the sex offender registry," she said. "One, it makes the person on the registry more stable and therefore less likely to commit a crime, something that they might not otherwise do if they had a place to live on a stable basis. And also for society's point of view, they will know where that person is actually living as compared to if somebody is homeless. They're going to sleep wherever they can and might be under a bush and might be behind a dumpster wherever they can find a place to sleep. And that, quite frankly, makes society less safe."

Belluci said that blocking someone from living in a shelter is unlawful.

"We haven't started suing shelters yet," she said. "But it looks like we might need to be starting to do that soon."

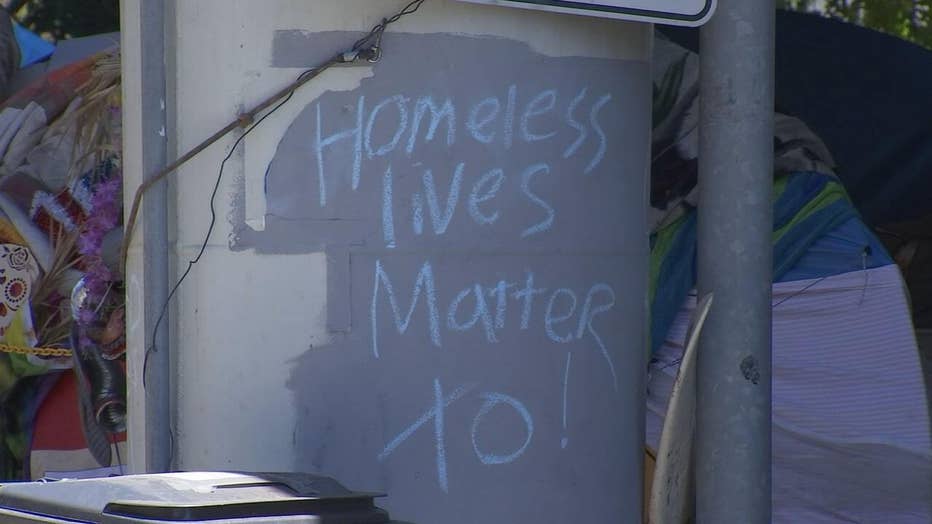

A homeless encampment under a freeway in San Rafael.

A homeless encampment in San Rafael.

Lisa Fernandez is a reporter for KTVU. Email Lisa at lisa.fernandez@fox.com or call her at 510-874-0139. Or follow her on Twitter @ljfernandez