Swollen lymph nodes can be side effect of COVID-19 vaccine and confused for cancer, doctors say

BOSTON - Swollen lymph nodes can be a normal and expected side effect after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, doctors say — and many are working to spread the word in an effort to ease patients’ fears of cancer and avoid unnecessary testing.

As coronavirus vaccines roll out across the U.S., doctors are seeing more patients with enlarged lymph nodes under the armpit, along the collar bone and even up into the neck. This natural response can occur on the side where an individual received their injection and was a recognized side effect in both the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNtech clinical trials.

It can also happen in response to other vaccines beyond COVID-19.

"It’s actually sort of a good sign that your body is responding to this vaccine and creating those great antibodies to fight off COVID virus in the event that you ever come in contact with it," said Dr. Constance Lehman, chief of Breast Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital.

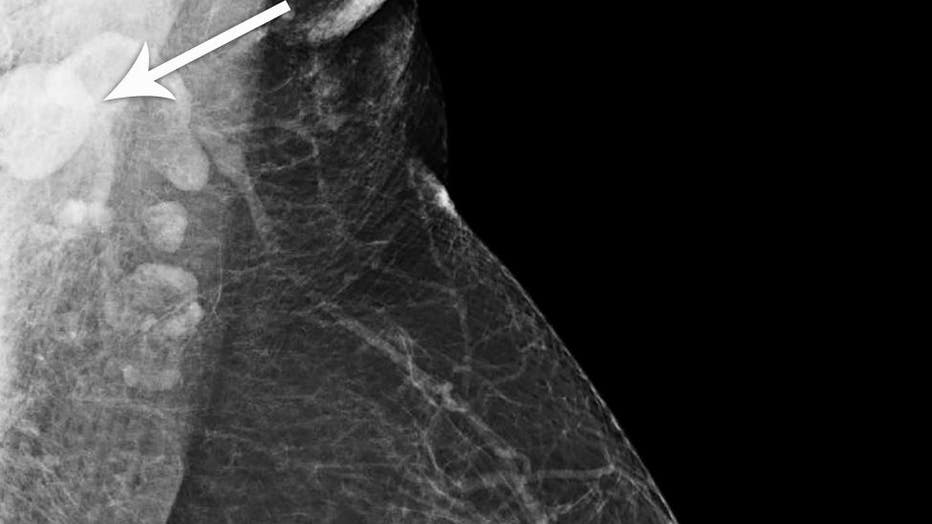

A provided image shows a left breast mammogram showing an enlarged axillary lymph node. (Photo credit: Massachusetts General Hospital)

Lymph nodes help the body fight off infections by functioning as a filter and trapping viruses, bacteria and other causes of illnesses.

Swollen lymph nodes usually occur as a result of infection from bacteria or viruses. In some cases, they can be an indication of cancer. The lymph nodes is one area that breast cancer most commonly spreads, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

In January, Lehman and her colleagues at the hospital’s breast imaging center in Boston began noticing more mammogram patients with enlarged lymph nodes while undergoing breast cancer screening. Prior to the pandemic, it wasn’t common practice to ask women about prior vaccines while getting a mammogram.

Soon enough, doctors throughout the radiology department at Massachusetts General began discussing this same occurrence in other divisions, such as abdominal and chest imaging.

"We were all thinking this was probably going to show up in all kinds of patients, not just ones coming in for a mammogram," she recalled, noting similar cases in a regular shoulder MRI and an ultrasound screening for another patient after having been successfully treated for thyroid cancer.

Lehman and her colleagues have since published journal articles on the topic and say it’s important for imaging centers to ask patients if they have received the COVID-19 vaccine, find out when it was injected and where it was administered in the body. If it was a two-dose vaccine, patients should share whether they most recently received the first or second shot.

In most cases, no additional testing is needed for swollen lymph nodes after recent vaccinations — unless the swelling persists or if the individual has other health issues. There is still more to learn as larger segments of the population are inoculated, but doctors think these symptoms should generally go away within six weeks.

They also share letters with patients in this situation, which reads: "The lymph nodes in your armpit area that we see on your mammogram are larger on the side where you had your recent COVID-19 vaccine. Enlarged lymph nodes are common after the COVID-19 vaccine and are your body’s normal reaction to the vaccine. However, if you feel a lump in your armpit that lasts for more than six weeks after your vaccination, you should let your health care provider know."

Lehman says they are seeking to spread the word about this while still at the beginning stages of the country’s mass vaccination campaign. Doctors hope to reduce unnecessary biopsies or additional imaging of lymph nodes — and prevent added anxiety for patients who may fear the worst without knowing about this vaccine side effect.

"The patients I feel, the most where my heart really goes out to them, are those in the midst of their cancer evaluation," Lehman said. "They’ve been told that they have cancer and then they notice that their nodes are swollen, and then the concern is, ‘Could this be malignancy?’ That raises such anxiety and such fear, and we want to tackle that right away."

Lehman said she also thinks of patients who have been successfully treated for their cancer and are now diligently going back for surveillance scans.

"That’s really hard when those patients hear, ‘We see something in your lymph nodes.’ So we want to get the information out," she added.

Still, there will be some cases that require a biopsy or additional imaging. Even though this response to the vaccine is normal, there will still be patients across the U.S. diagnosed with lymphoma, metastatic breast cancer or some other metastatic cancer.

"At one extreme, centers have been very concerned about lymph nodes and even went to the extremes of biopsying the lymph nodes to make sure that they weren’t cancer. That’s really an extreme that we’re all trying to stay away from. But the other extreme, people were saying it’s always about the vaccine and don’t worry about it at all. Just continue on as you always have been, and that’s an extreme where we don’t want to land either," Lehman said.

Some in the field have suggested delaying routine imaging for at least six weeks after the last dose of vaccine. Lehman believes this should be a local community decision based on the resources available — but noted the thousands of women who already missed their routine mammograms in 2020 due to the pandemic.

"We’re trying to get them in now. I don’t want more barriers," she said. "I think it’s so important that we just get our patients in."

Those who have not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine can request to have the injection on a particular arm or even in the thigh, as approved by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For those who have been diagnosed with cancer in the past or are currently going through treatment, Lehman said to consider asking for the injection to be farthest from the sight of where the cancer is located in the body.

"That way, the area where we would be worried about lymph nodes the most on the side near her prior breast cancer is sort of spared from that reaction. People can use the same logic if they had cancer in another part of their body," she said.

Many expert medical groups recommend that most people with cancer or a history of cancer get the COVID-19 vaccine once it’s available to them, citing a risk for severe illness in those with a more fragile immune system. But as always, patients should discuss this with their doctor.

"If you haven't been vaccinated yet, as soon as you can get in line and get vaccinated. Don't worry about the sequella of having the vaccine and then having other imaging done. We want you to get vaccinated," Lehman said.

This story was reported from Cincinnati.