Mendez v. Westminster: How a family fought school segregation -- and won

Mendez v. Westminster: How a family fought school segregation -- and won

FOX 11 spoke with Sylvia Mendez – who at age eight -- played a pivotal role in the Mendez v. Westminster case, the landmark desegregation case of 1946.

ORANGE COUNTY, Calif. - Several years before Brown v. Board of Education, there was Mendez v. Westminister.

The landmark case sparked a domino effect that opened classroom doors for children of color across the nation.

The child at the center of it all is now 85 years old and still lives in Orange County.

"I want them to remember that people have always been fighting for equal education and equality," said Sylvia Mendez.

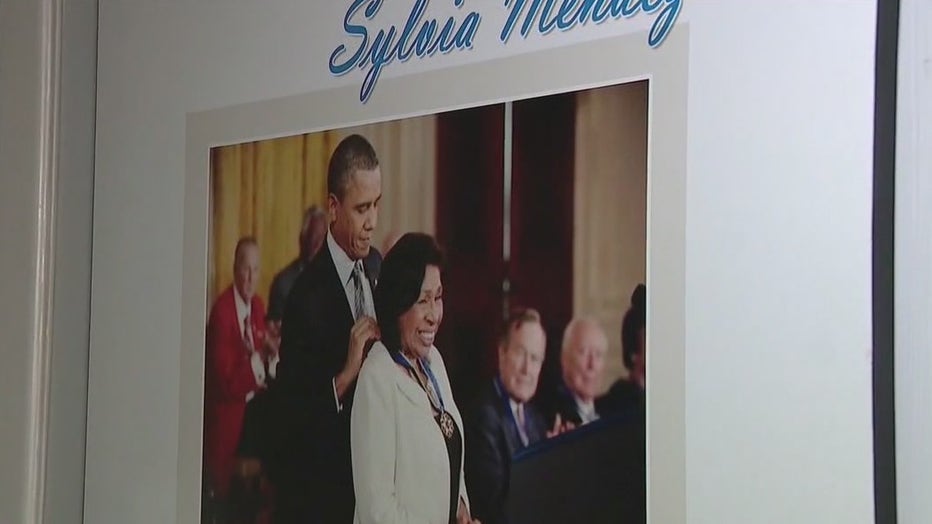

She showed us a room in her Fullerton home where she keeps all the honors she and her parents have been bestowed on. There’s a photo of her with President Barack Obama giving her the Medal of Freedom, there are pictures of President George W. Bush hosting her at the White House. There’s also a children’s book about her case, even a postage stamp, but there’s still one honor that eludes her: she wants her parents' fight memorialized in California textbooks.

Get your top stories delivered daily! Sign up for FOX 11’s Fast 5 newsletter. And, get breaking news alerts in the FOX 11 News app. Download for iOS or Android.

In 1944, her father Gonzalo Mendez – who was of Mexican descent – and her Puerto Rican mother Felicitas moved back to Westminster.

Her father had grown up there but had left to start businesses in Santa Ana. Mendez explains he returned to right an injustice. He had decided to lease a ranch from the Munemitsu family, who were of Japanese descent and were placed in an internment camp.

Get your top stories delivered daily! Sign up for FOX 11’s Fast 5 newsletter. And, get breaking news alerts in the FOX 11 News app. Download for iOS or Android.

Sylvia’s aunt took her and her cousins to enroll in the local school. She still remembers an official there saying her light-skin cousins could attend but she’d have to go to the Mexican school.

"My aunt got so upset. She said, ‘What do you mean?’" Mendez said. "I’m not going to leave my kids here if you won’t take my brother’s kids."

Gonzalo Mendez, a sucessful businessman hired an attorney who had sued the City of San Bernardino over barring Mexicans from public parks.

Mendez says the two men then strategized and started a class action lawsuit. Gonzalo went about recruiting friends and family members to join in.

"Who could forget the Mexican school?" Mendez said, recounting how she watched a classmate writhing and shaking after accidentally grabbing at an electrified fence at the school, which was meant to keep nearby cattle herds out.

At 8 years old, she says she was being taught domestic skills in class, not academics. That’s why her father spent most of the money he’d amassed, fighting the case.

He paid wages to fellow litigants so they could be in court and not lose a day's pay. Sylvia and her siblings were also in the courtroom teasing each other as the lawyers argued the case.

She said at one point, school officials approached her father to settle the case.

"We’ll let your kids go to the white school, just stop all this," Mendez recounts officials telling her father. "And he says, 'No, I’m now fighting for all the children."

Sylvia was about 10 in 1947 when they prevailed in court and a white school in Santa Ana was forced to accept her. While the case was argued, the Munemitsu family had come home and the Mendez family had moved to Santa Ana, where another school had refused to admit her.

The court victory led to the desegregation of California schools and inspired Thurgood Marshall’s arguments in Brown v. Board of Education.

"It was nothing like what happened in the South like what happened to all those people," she said. "But I do remember this little white boy saying to me, 'Ew, what are you doing here? You’re Mexican."

She also remembers the white classmates who were kind and invited her to parties.

"What I learned at that age is that not everyone is prejudiced," she tells us.

But what she didn’t fully grasp as a child was the importance of her case. After complaining she didn’t want to go back to school she says her mother asked her if she knew why they’d gone to court.

"So I could go to the white school with monkey bars and swings," she recalls telling her mother. "She says Sylvia that’s not all why we fought. "

Adding her mother explained that everyone deserved equality and were the same in God’s eyes.

Decades later Mendez, now a retired nurse, wants her parent’s story told.

Her own sister, who was born after the case, never knew her family’s role until she read it in a Chicano Studies class at UC Riverside.

Mendez says her parents never discussed it but she wants today’s children to know how hard they fought and how much they sacrificed. She says after the case there was no money left.

Educators are free to teach history in class. But in 2008, then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed a bill that would have included the case in state textbooks.

He wrote at the time, "While I respect the author's intent to recognize the role that the Mendez v. Westminster School District case played in the civil right movement, I have consistently vetoed legislation that has attempted to mandate specific details or events into areas of instruction."

"I was so heartbroken, I cried for a week," said Mendez. "Why would he do that?"

The district that once fought to keep her out is now teaching her case in the classroom.

There are also schools that now bear the Mendez name, but the children who fill them are overwhelmingly Latino. De facto segregation is still a reality, Mendez says. And like her parents, there are other families still fighting.

"The 14th Amendment says we’re all equal," she said. "That we all deserve the same education, the same kind of treatment."

Tune in to FOX 11 Los Angeles for the latest Southern California news.